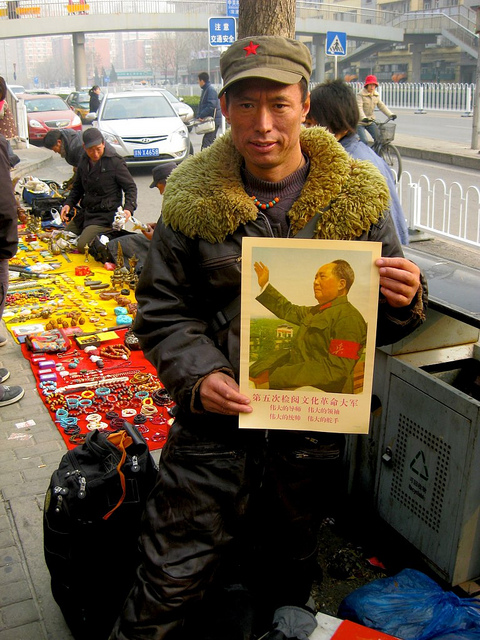

Zha Xi is a Tibetan migrant who moved to Beijing several years ago in search of better economic prospects. A Buddhist, he is part of a group of Tibetan migrants who sell Tibetan artifacts and Chinese propaganda posters in Beijing. The posters, which are copies of posters printed in the 1960s, proclaim various messages intended to glorify Mao Zedong, strengthen the Party’s position in society, and unite the common people.

These days, the posters are a popular item among the foreigners who pass by Zha Xi’s sidewalk sales operation in the heart of Wudaokou, Beijing’s university district. He usually earns about 1,000 RMB a month ($150), significantly more than he would have in his village. We spoke with him to gain some insight into his life and his views regarding his wares.

Where are you from?

A village in Sichuan province, on the border with Tibet. There are about 500 people in my village.

Can you describe your childhood and your life in your village?

My family is very poor. I am the youngest of five children. They are all farmers who grow a special kind of Tibetan wheat. They live in a two- story self-constructed home built of stone.

How much money does your family farm make per year?

The farm doesn’t really make any money, since anything we save is spent at the end of the year, when we buy a new cow. A cow is 2,000 RMB ($300).

How much schooling did you receive? Which languages can you speak?

I attended elementary school for three years, from the age of eight until I was eleven. I can speak Tibetan and Mandarin Chinese. In Mandarin Chinese, I understand the characters for numbers and the characters for male and female. I can read a little of the Tibetan script.

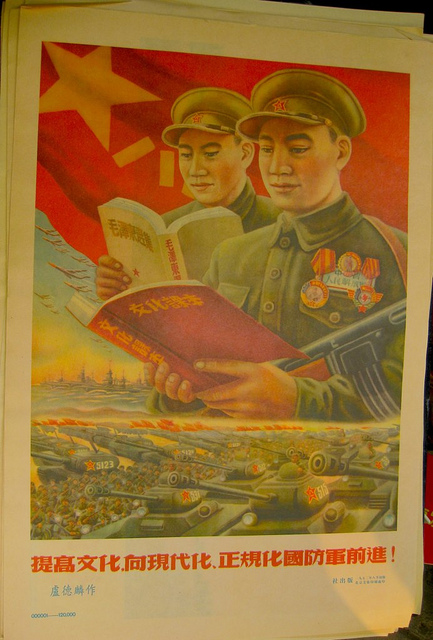

Improve the culture, march toward the modernization and standardization of the People’s Liberation Army

Why did you move to Beijing? How did you hear about this job?